A great campaign, with few exceptions, begins with solid plan. Here's how to make one.

Several people spanning sundry skill sets need to come together in harmony to produce great campaigns, and harmony is better achieved if everyone is reading off of the same sheet of music, so to speak. Without that, time and money are wasted, quality invariably declines and results suffer. This article outlines some tried and true practices to follow when planning for your marketing campaigns.

The Creative Brief

For the best possible, most consistent results, always work from a brief. Without the brief, everything is a moving target.

Even if you think you’ve got it all in your head, take the time to get it all down on paper, in a consistent format that has proven to work well for your organization. Faithfully following this practice ensures that you aren’t missing anything and that expectations are leveled with all team members and stakeholders.

Who Writes the Creative Brief?

In a traditional, big-agency environment, the account planner or account exec writes the brief. However, it has been my long-held belief that everyone on the team should know how to craft one.

Designers and copywriters benefit from this skill because they can’t always count on a good strategy to be handed to them, and at the very least, they should be able to back check the briefs supplied to them.

Any other stakeholders will be more productive participants if they are familiar with the constructs and process of writing briefs.

Many ad planners and marketers have their own preferred flavor of brief. Mine was derived from various sources over the years and has proved to be a reliable format time after time.

Before I touch on each section of my creative brief format, I can’t overemphasize the importance of keeping it, well, brief. Mark Twain is often credited with a famous quote about wanting to write a shorter letter, but not having the time. Granted, it’s difficult to communicate clearly with as few words as possible, but a great brief should do just that. Hence the name. With that, following is a quick description of each section in my creative briefs:

Section 1: Background/Overview

In this opening section, explain the situation. Who’s asking you to do what, and why? Why are you creating this campaign at all?

It can also help to quickly describe the ad media, placement, and timing in this section.

Section 2: What are the objectives of the communication?

Objectives can be thought of in so many different ways. I’ve found it most helpful to list the high level business objectives here, in measurable terms if possible.

Supposing Dyson was running a brand awareness campaign, one way of answering this question may be to say “raise brand awareness”. A better way may be to say, “Persuade our audience to consider Dyson as the most innovative makers of vacuum cleaners and take the time to learn more.”

People learn on their own terms in all sorts of different ways. Thankfully, digital technologies allow us to track and monitor key events that signal when prospects enter the knowledge and consideration stages of the buyers' journey. Today's marketers are expected to use that data to measure the effectiveness of campaigns relative to its objectives. If your job performance is tied to the measurable outcomes of the campaigns you're running, you'll want to be extra thoughtful, and crystal clear about the campaign's objectives. And there's no better time and place to do it than in the campaign planning stage, and documenting them in the Creative Brief.

Section 3: Who are we talking to?

In describing the target audience, a common mistake is to stop short after listing a few simple demographics. Good briefs go beyond that to include a certain mindset, situation or intent on the part of our audience that helps us narrow our focus.

For the Dyson brief, we may say something like, “quality-conscious, design-minded adults across the United States that are in the market for the best vacuum cleaner that they can get.”

All vacuum cleaners are garbage. They are heavy, clunky, and hard to move around. I’m tired of them getting clogged and losing suction."

Section 4: What do we know about them that will help us?

This is one of the most important sections of the brief because great campaigns should speak directly to prospects’ preconceived wants and needs. Below is a quick checklist to help you fill out this section. I’ve included examples in italics of how each item may be answered for the Dyson brief, from the prospect’s point of view.

Describe prospects’ preconceptions of the product category.

“All vacuum cleaners are garbage. They are heavy, clunky, and hard to move around. I’m tired of them getting clogged and losing suction.”

Describe prospects’ preconceptions of our product in particular.

“Dyson’s products look well designed and they claim to have innovative, proprietary technology that prevents them from ever becoming clogged.”

List prospects’ preconceived wants and needs from the product category.

“I want a well-designed, high-quality, light weight vacuum cleaner that works fast on my expansive floors and won’t clog. I don’t care if it costs more, I want it to work, and last a long time.”

Highlight which of those we can legitimately meet with our product.

All of them, however the lightweight model may not provide fast coverage of large floor space.

Section 5: What is the main idea that we need to communicate?

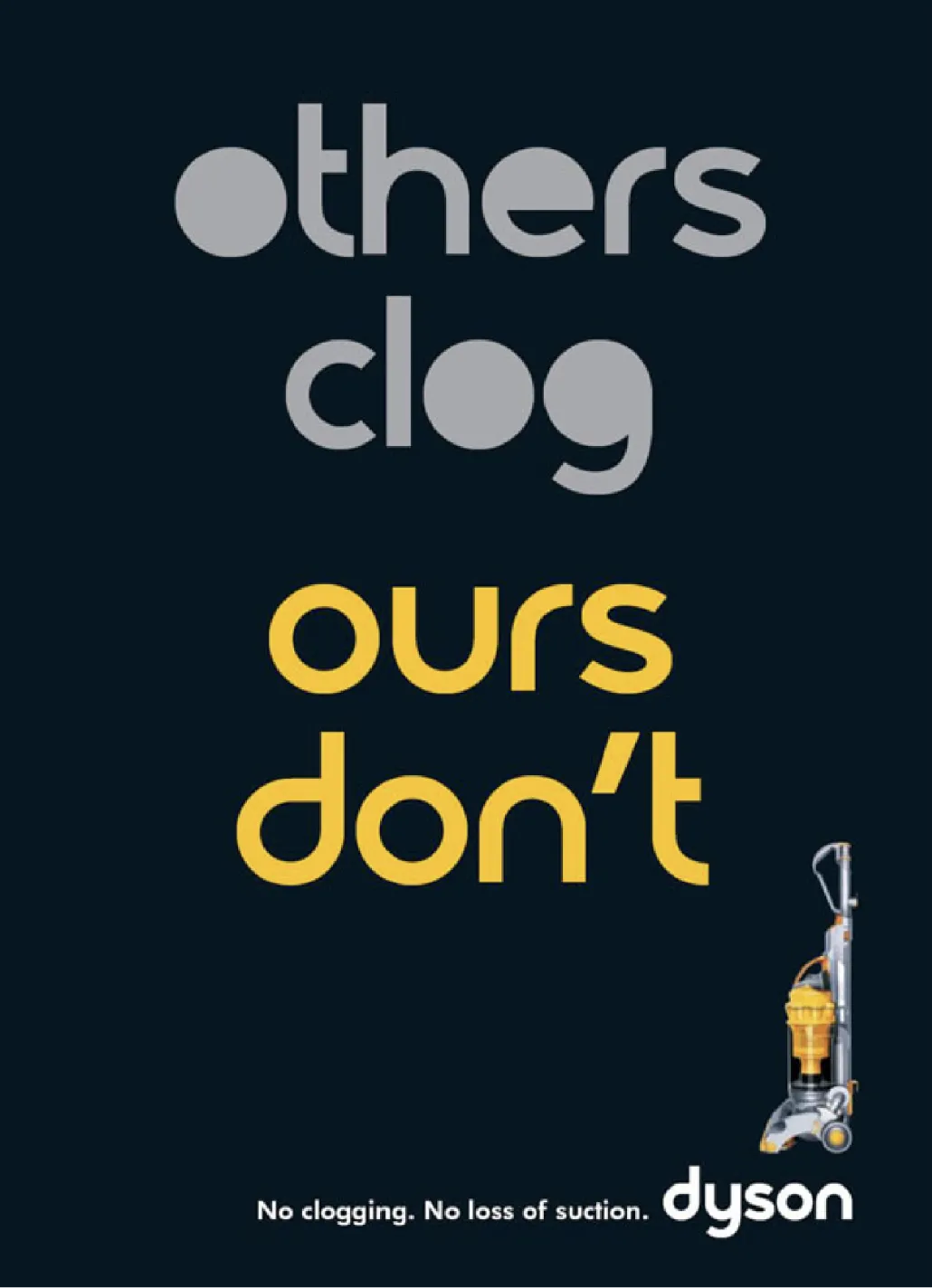

These are key messages that you want your prospects to absorb. They should achieve business goals while speaking directly to prospects’ preconceived wants and needs. One main idea is best to give the ad focus—don’t try to say too much in your main message. For the Dyson brief, here we may say “Dyson vacuum cleaners don’t clog like all of the other ones do.”

Section 6: What is the best way of presenting the idea?

This section should be high-level. Don’t try to solve the creative problem here. Dyson’s brief could say:

"A simple, clever, memorable print ad that gets the main point across and conveys a sense of high design."

Section 7: Why should they believe us?

This is where you want to list any and all supporting evidence that could be used in the ad to drive the main idea home.

Even if these proof points don’t explicitly make it into the ad, by listing them here, we will know that our claims can be backed by facts. Dyson’s brief could include patent info, results from controlled studies, etc.

Section 8: What action do we want them to take?

Not including a suggested next step in the purchasing process or customer journey is almost always a waste. In the Dyson brief, we would want them to go to dyson.com to learn more.

A friendly url that is unique to the ad, like dyson.com/noclog, would allow Dyson to track traffic to their site that originated from the campaign.

Section 9: Design imperatives.

In this final section, list any important constraints or must haves. Examples can include things like: comply with brand standards, extend the creative from another campaign, show a particular image of the product or some other mandate, perhaps put forth by the client. The Dyson brief may remind the designer to include a beauty shot of a certain product model, continue the black background theme from the other campaigns that ran the same year, etc.

Socializing the brief

Once the brief is drafted, it’s important to share it around with the team and get their buy in, because one of its most important functions is to serve as a contract between all stakeholders.

Once the brief has been approved, then the team can be held accountable to centralized success criteria and anyone providing feedback on creative ideas will need to rationalize their opinions against the mutually agreed upon strategy described in the brief.